Will the Legislature Permit Local Ranked Choice Voting?

Brookline, Arlington, Lexington, Concord, Acton, Amherst, and Northampton have all submitted Home Rule Petitions (HRPs) to the State House asking to let town voters decide whether to adopt Ranked Choice Voting (RCV) for local elections. These petitions are currently with the Joint Committee on Election Laws on Beacon Hill, awaiting approval so the main body of the Legislature can vote on them. The current word is that several of these Home Rule Petitions will not be allowed forward. Many residents of these towns and cities still hope to hear otherwise, however, and much discussion is taking place in these communities about why the Joint Committee would not move these HRPs on to the main body of the legislature. Although the Joint Committee debates behind closed doors, some information is known. In the realm of political strategy and power dynamics, the Massachusetts Legislature's reluctance to pass Home Rule Petitions for local Ranked Choice Voting is a fascinating study. The inaction that seems likely not only mirrors the broader challenges of electoral reform but also provides a window into the dynamics of legislative decision-making and the preservation of political power in our state.

A Brief Background of RCV in Massachusetts

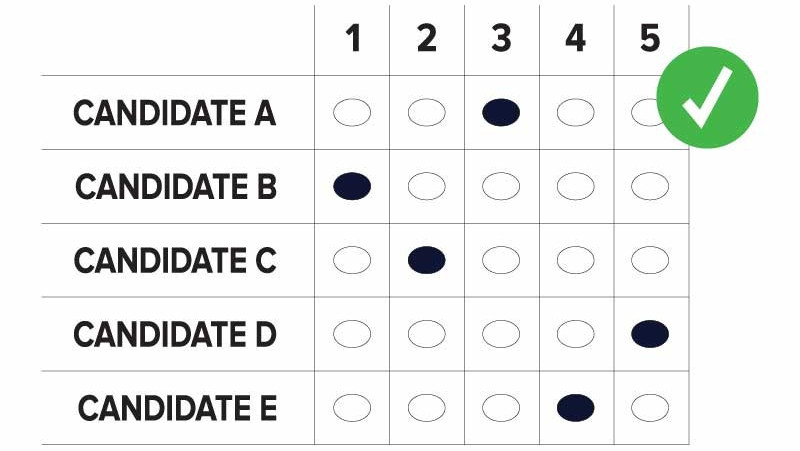

Ranked Choice Voting is intended to solve many of the issues we experience with first-past-the-post voting, and it has a long history of use in Massachusetts. Cambridge, MA, stands out as a pioneering city in this regard, having adopted a form of Ranked Choice Voting in 1939. This use of RCV in Cambridge serves as an example of its applicability and success at a local level, yet other municipalities have faced challenges when looking to use RCV in their own communities.

Some may remember a major statewide initiative, known as Question 2, which was presented in the 2020 Massachusetts general election. This initiative proposed changing elections in Massachusetts from first-past-the-post plurality voting to RCV for all state legislative offices, federal congressional offices, and certain other offices beginning in 2022. However, the initiative did not pass, with 54.8% of Massachusetts voters voting 'No' and 45.2% 'Yes'.

This defeat indicated that significant hurdles exist in the statewide adoption of RCV. Despite the statewide setback, though, Massachusetts has witnessed local movements embracing RCV. The idea is that, although some MA communities do not want RCV, communities like Brookline, where a majority of voters supported Question 2, should be allowed, like Cambridge, to decide whether to use RCV in their local elections. Why would it be controversial to allow a community which wants to use RCV in their municipal elections a vote to decide that?

The "Municipal Disinterest" Argument

The view held by some state legislators that they should not support local RCV initiatives because they were not favored at the state level is a challenging one to overcome. This perspective contests the principle of local autonomy and self-governance. It is not difficult to see how the two topics, while both about RCV, are separate. Home Rule Petitions are designed to allow communities to tailor their electoral systems according to their specific needs and aspirations. Should the potential lack of interest in RCV in Haverhill, where 40% of voters supported Question 2, impact the ability to hold a vote on adopting RCV for local elections in Amherst, where RCV support was 76%? It is hard to see where this question does not boil down to one community deciding for another how that municipality should vote.

Moreover, this viewpoint does not account for the evolving nature of public opinion. Electoral reform has many examples where local movements have gradually garnered broader support as people learned more about the initiative, fundamentally reshaping national policies over time. Once people use RCV, many of the fears about its complexity are often relieved. Legislators are frequently responsive to emerging trends and local sentiments, rather than being anchored to past voting outcomes. Why is RCV different?

Power Dynamics at Play

For many legislators, the predictability of the current system, despite its limitations, is preferable to the uncertainties introduced by RCV. Ranked Choice Voting is a system where voters rank candidates by preference. It frequently leads to selection of more moderate candidates which better represent the views of their constituents and is a shift from traditional plurality voting. This shift is not merely procedural; it can alter the political landscape, challenging a status quo that benefits incumbent politicians. From a strategic standpoint, the reluctance to allow RCV even at the local level has its roots in power preservation. Incumbent politicians have succeeded within the existing voting system. The shift from a plurality system to a ranked system could disrupt established voting patterns, coalitions, and campaign strategies, resulting in comfortable incumbents having to deal with challengers in primaries.

Maintaining control over uncertainties is a key aspect of power dynamics. For many politicians, the known, even with its flaws, is preferable to a system that could jeopardize this position. In a state where one party outnumbers the other in the legislature by about four to one, the idea of giving even a local nod to a voting system that may lead to less power is bound to meet resistance.

Resistance to RCV also stems from a lack of perceived direct benefit among legislators, since in order to move legislation forward they must be cognizant of how much political capital to spend with peers and legislative leaders given other priorities they are trying to accomplish. If RCV momentum might lead to a needed colleague being less likely to be elected, a legislator will be less likely to support it. This perspective was candidly expressed by lawmakers who doubted the possibility of persuading colleagues to endorse HRPs for local RCV since those other legislator’s municipalities had not supported RCV at the state level.

Strategizing the Path Forward for Local RCV

To effectively address the impasse in the adoption of Ranked Choice Voting at the municipal level, advocates need to engage in a two-pronged approach that not only communicates the benefits of RCV but also addresses the fears and concerns of legislators about their electoral security under this new system.

Advocates must intensify efforts to educate both legislators and the public about the intrinsic benefits of RCV. This includes highlighting how RCV can lead to more civil campaigning, a reduction in negative advertising, and the encouragement of diverse candidate participation. Moving away from first-past-the-post voting methods is a step towards a more inclusive and representative democratic process. By demonstrating that RCV can create a more positive and inclusionary political atmosphere, legislators might be less fearful of the system as a threat and more as an opportunity for healthier democratic engagement.

One of the primary concerns among legislators is the fear of losing their positions if RCV is implemented. Community members and RCV proponents should address these fears directly. They should reassure legislators that RCV, by encouraging a broader appeal to a wider constituency, can actually strengthen a candidate's electoral positions if they are responsive to their voters' needs. Advocates should remind legislators that true power and longevity in politics comes from being responsive and accountable to constituents, rather than relying on the mechanics of the current voting system to maintain elected positions. By allowing RCV to be implemented at the local level in the municipalities who have voted for it legislators can demonstrate their commitment to democratic fairness and their willingness to evolve with their constituents' preferences, thus solidifying their standing as representatives who prioritize the will of the Massachusetts public.

Proponents of RCV must navigate existing power structures effectively. This involves identifying allies within the legislature who are open to or supportive of RCV and mobilizing public support. Seeing that public opinion is in favor of RCV (or at least, in favor of allowing the communities which want to use it to do so) legislators will be more compelled to support it, recognizing that their electoral success is tied to the public's perception of their adaptability and openness to democratic reforms.

Final Thoughts

The Massachusetts Legislature's hesitation to pass Home Rule Petitions for local Ranked Choice Voting is a complex topic, deeply rooted in the interplay of power dynamics, resistance to change, and political strategy. However, by addressing these concerns, emphasizing local autonomy, and skillfully navigating the legislative landscape, there is a path forward for local RCV advocates to facilitate meaningful change in their towns and cities. If Maine and Alaska can do it, why not Massachusetts towns? Through well thought out advocacy and education, the adoption of RCV at a local level can become a reality, paving the way for a more representative and dynamic democratic system in The Commonwealth.

If you would like to know more, please contact your local legislator or the Joint Committee on Election Laws at this link, and ask them to move Home Rule Petitions for RCV forward when asked to do so by our Massachusetts communities.

If you found this topic interesting, please let me know by clicking here to support my writing.